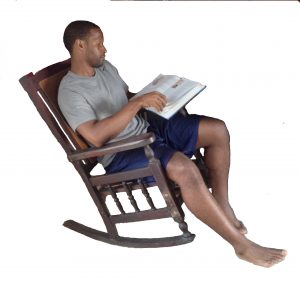

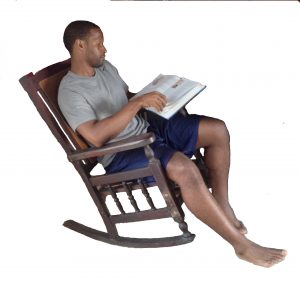

Pasha Jackson, a former linebacker with the Sooners, now studies medicine in Cuba. Photo: Isaac Eger

By Isaac Eger

Pasha Jackson prides himself on punctuality, so when he arrived 20 minutes late to the interview, he asked for forgiveness.

“I got held up by some heavy Cuban stuff,” Jackson, 31, said.

The former NFL player, who still looks like a world-class athlete, is in his fifth and penultimate year of studies at the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) in Havana, Cuba. The Chicago native is one of 10,000 students from over 70 countries with low-income backgrounds — including some 200 from the United States — whose room, board and education are paid for in total by the Cuban government.

The heavy stuff that delayed Jackson was a breakthrough in his three-week pursuit of a rocking chair.

“All the chairs in my house sit awkwardly, and I want to sit down comfortably to read my books,” Jackson said. “So I’ve been wheeling and dealing; I’ve talked to four different neighbors, two carpenters and many people with broken chairs.”

On his way out the door, one of Jackson’s neighbors called his name and told him that he found someone with a dilapidated rocking chair they would let him refurbish at his own expense.

“I didn’t know when that situation was going to arise again,” Jackson said, “but that’s what it’s like when you need to resolver.”

Resolver is a Cuban expression that became prominent during the Special Period when the country’s economy was in shambles. The word implies ingenuity in the face of scarcity, and though Cuba is better off today, resolver-ing is ingrained in the island’s culture.

Jackson had to resolver long before he arrived in Cuba in 2008. At the age of three, he moved to California with his father, who had to go to extremes to keep Pasha and his brother and sister afloat.

“I don’t have enough fingers to tell you the places that we moved,” Jackson said. The constant uprooting left Jackson yearning for a sense of fraternity. He found his community on the football field. Belonging to a team gave him comfort, and his physical abilities took him all the way to the Oklahoma Sooners, where he played linebacker for the BCS champions. He signed four different contracts with four separate NFL teams: the 49ers, the Colts, the Chiefs and the Raiders, but politics and injuries kept Jackson from becoming a permanent member of any club.

Jackson eventually went to Europe where he played for the Amsterdam Admirals. Then, in 2005, during a kickoff, Jackson’s left pectoral was torn from the bone. Back stateside, while laid up in a Birmingham, Ala., hospital, Jackson decided to take some time away from football.

Cuba, not Mexico

“I wanted to develop myself outside of football, get away from the sport for a while. I figured that learning a second language would be great.”

Jackson told his father, now a tenured professor of psychology, that he wanted to go to Mexico. Dad asked him if he’d consider Cuba instead.

His father had a long history with black community activism and was inspired by Cuba’s medical internationalism — “the role [Cuba] played in the fight against Apartheid in South Africa, and the time when they tried to help my family out during hurricane Katrina that [President George W.] Bush ended up turning back,” Jackson said.

Through a quick internet search, Jackson was introduced to the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO) and their Pastors for Peace program, which has sent U.S. students to attend ELAM since 2000.

He became one of them in August 2008.

Fidel Castro created the ELAM in 1999 as a means to promote Cuba’s free healthcare principles, and project a positive image of Cuba on the developing world. The campus, located on the western edge of Havana, was once a naval base, but now its barracks are filled with medical students from around the world.

“The campus is gorgeous and right by the water. They transformed a naval base into a medical school; how poetic is that?” Jackson said.

Students’ entire education is funded by the Cuban government, including supplies and textbooks. They even pay a small stipend of $5 monthly to each student- — roughly one-fifth of the salary of the majority of local doctors.

Free medical education was a tenet of the Revolution, and in five decades, Cuba has created one of the best primary care systems in the world, boasting the highest doctor-patient ratio of any nation. Cuban doctors are sent around the world to educate and heal people in poor and backwater areas, as a form of medical diplomacy.

No standardized patients

“I feel Cuban when I go back to the States,” Jackson said. “I feel strongly American when I come back here.” Jackson’s daily life is no different from the life of any other international student at ELAM. He attends classes, reads his books and when he finds time for himself, he practices yoga.

The Cuban form of medical education is much different from what Jackson has encountered in the United States. Last summer, he went back home to Oakland, Calif. to practice for his second board exam at the Samuel Merritt Hospital. At the school, Jackson was surprised to discover that he had to practice on standardized patients.

“They have actors that pretend to have diseases … I was flipping out because I’d never dealt with a patient who was not actually sick in their eyes, in their soul.”

Not so in Cuba.

“I could put on scrubs right now, go to any hospital in the country, show my ID and then just go.”

Jackson has access to all hospitals and can observe and assist any doctor. “The whole county is a med-school.”

Jackson is inspired by the Cuban medical system and the doctors he has worked with in Havana.

“They are here to serve people. They are not all-powerful, all-knowing, looking down. What we are doing is working side by side, serving people.”

The only post-graduation commitment the Cuban government wants from students is a pledge to return home to practice in underserved communities.

When money is no longer the main driving force for physicians, “the notions of servitude, humanitarianism and altruism related to the profession are more clearly defined. Cuban doctors’ overall fulfillment must come from other recompenses.”

Targeting CTE

In 2015, Jackson will graduate and return to the United States with a doctorate in medicine from ELAM. He will be eligible to apply to any U.S. residency program by enrolling in the National Resident Match program, which is like the NFL draft for doctors, hoping to find a good fit with a hospital.

Jackson’s focus is on family medicine and geriatrics, but he wants to use his experience with medicine and football to confront CTE, the concussion-induced condition that afflicts many athletes.

“[CTE] really has my attention because I am someone who has suffered serious, repeated brain trauma.”

Four weeks and $10 later, Jackson had his rocking chair. “I learned how much waiting is an integral part of society,” Jackson said. “There is no Cuban who has not gone to the Cuban school of patience.”

Thanks to the rocking chair, Jackson earned that degree.

Isaac Eger is a freelance journalist based in New York who writes about sports

ELAM Resources

ELAM students from the United States apply through IFCO/Pastors for Peace. U.S. applicants need one-year, college-level coursework in biology, physics, and organic and inorganic chemistry (all with lab). They must fill out a form, supply letters of reference, a personal essay, and medical history, and go through an interview.

U.S. students graduating from ELAM can count on the help of Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC), an Oakland, Calif.-based non-profit. MEDICC provides returning students fellowships to defray costs of U.S. board exams and preparation. The organization also teams graduates with mentors to guide them into residency and successful medical careers in the United States.